As part of the Didaktika project, the Museum designs educational areas and organizes activities to complement its exhibitions. Tools and resources are provided both in the galleries and online to increase viewers’ understanding and comprehension of the artists and works on display.

In the early 20th century, research on the human brain was making great strides. In Germany, the practice led by neurologist Korbinian Brodmann (b. 1868; d. 1918) identified up to 52 functional areas in the cerebral cortex. In the USA, Harvey Williams Cushing (b. 1869; d. 1939) was a pioneer in neurosurgery. His predecessor was the Spaniard Santiago Ramón y Cajal (b. 1852; d. 1934), Nobel Prize winner in Medicine in 1906, whose contributions to our knowledge of the central and peripheral nervous system made him the forerunner of modern neuroanatomy.

Simultaneously, approaches questioning the capacity for reason and tangible reality were also emerging. Sigmund Freud (b. 1856; d. 1939), the father of psychoanalysis, had been trying to explain the subconscious since the early 20th century. Studies of the psyche truly blossomed during this period.

Of all the scientific innovations, perhaps the most important one was the discovery of penicillin by Alexander Fleming (b. 1881; d. 1955) in 1928, a fact which fueled the optimism of a society that had been brutalized by pandemics like the “Spanish Flu” in 1918–19, which took the lives of millions of people all over the world. Can you see any similarity with the present day?

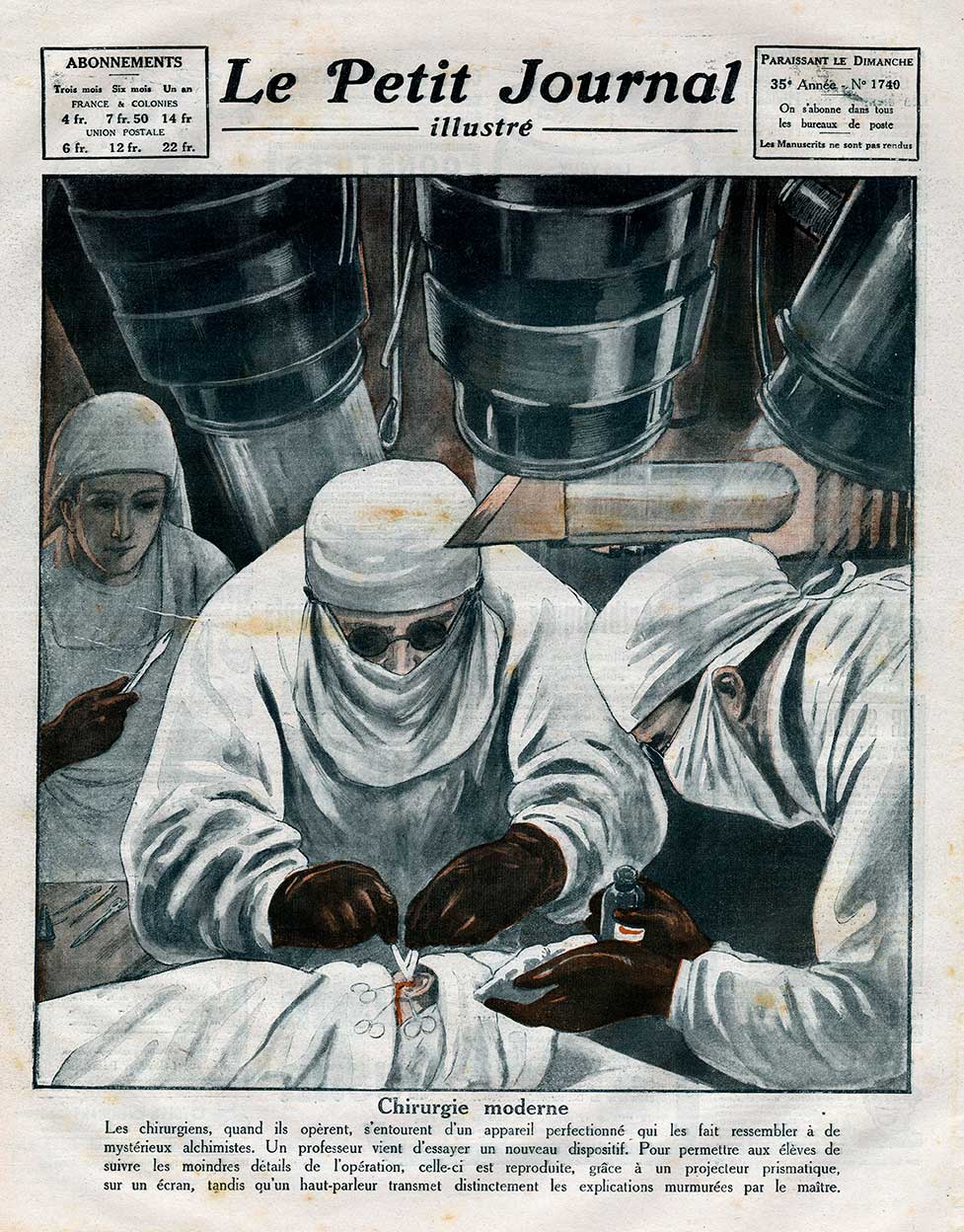

Surgery professor operating with the aid of a visual and aural system that allows students to watch live on a screen. Front cover: Le Petit Journal —Illustré—, 1924. Photo: Leemage. Getty Images.