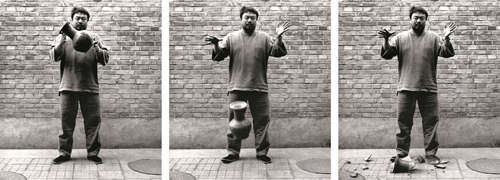

Ai Weiwei, Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, 1995

Participatory event for 1,001 Chinese citizens to go to Kassel after being recruited through the Internet, as part of the project organized by Ai Weiwei for Documenta 12

Ai Weiwei, Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, 1995. Three gelatin silver prints, 148 x 121 cm each. Courtesy Ai Weiwei Studio © Ai Weiwei

Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World is a large exhibition of contemporary art from China that spans the years 1989 to 2008, which can be seen as the most transformative period of modern Chinese and recent world history. The period extends from the end of the Cold War and the spread of globalization to the rise of China as a global presence, culminating in the 2008 Beijing Olympics. The exhibition highlights approximately 70 key Chinese artists and artist collectives and features nearly 150 experimental works in film and video, installation, painting, sculpture, photography, performance, and socially engaged art and activist art. The show is organized in six chronological and thematic sections occupying the second floor at the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao.

“It’s powerful only because someone thinks it’s powerful and invests value in the object.” [1]

Artist, thinker, and activist Ai Weiwei was born in Beijing in 1957 and grew up in difficult circumstances. His father, the poet Ai Qing, was persecuted by the Chinese Communist government and exiled to a far western province. He was later hailed as a great national poet after the death of Mao Zedong in 1976. In 1981 Ai moved to New York, where he studied visual art and began working as an artist. He also developed a deep appreciation of Marcel Duchamp’s “readymades”—found objects of everyday use elevated to the status of art—and their implied critique of cultural value systems. In 1993, upon learning that his father was ill, he returned to China.

One of Ai’s most famous pieces, Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn (1995), incorporates what Ai has called a “cultural readymade.” The work captures Ai as he drops a 2,000-year-old ceremonial urn, allowing it to smash to the floor at his feet. Not only did this artifact have considerable value, it also had symbolic and cultural worth. The Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) is considered a defining period in the history of Chinese civilization, and to deliberately break an iconic form from that era is equivalent to tossing away an entire inheritance of cultural meaning about China.[2] With this work, Ai began his ongoing use of antique readymade objects, demonstrating his questioning attitude toward how and by whom cultural values are created.

Some were outraged by this work, calling it an act of desecration. Ai countered by saying, “Chairman Mao used to tell us that we can only build a new world if we destroy the old one.” This statement refers to the widespread destruction of antiquities during China’s Cultural Revolution (1966–76) and the instruction that in order to build a new society one must destroy the si jiu (Four Olds): old customs, habits, culture, and ideas. By dropping the urn, Ai lets go of the social and cultural structures that impart value.

Preguntas

Show: Ai Weiwei, Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, 1995

Ask students to describe what is happening in this work.

Discuss the meaning of Ai’s statement regarding this work: “It’s powerful only because someone thinks it’s powerful and invests value in the object.”

How has Ai used elements of shock and surprise in this work?

These photographs of Ai dropping a 2,000-year-old Han dynasty urn capture a moment when tradition is challenged by new values. Some might view this act as pure vandalism, while others will see it as an artistic statement that challenges the status quo. Discuss and debate these questions with your students. Which aspects of tradition do they think should be preserved? Which traditions do they think should be reexamined and revised?