100% Africa

10.12.2006 - 02.18.2007

Since 1989, the Swiss photographer and businessman Jean Pigozzi has amassed an extensive collection of contemporary African Art which, with the collaboration of curator André Magnin, became the Contemporary African Art Collection (CAAC). This exhibition presents a selection of works from this well-known collection, which spans a wide spectrum of artistic creation from the African continent and contains a diversity of forms of expression. The exhibition includes the work of twenty-five artists such as Frédéric Bruly Bouabré, Bodys Isek Kingelez, Chéri Samba, and Malick Sidibé, among others, from twenty sub-Saharan countries, and also presents a large number of recent pieces never seen before as well as works that have been specially commissioned for this show.

Contemporary African Art

Presented by the Contemporary African Art Collection in Geneva, 100% Africa is a varied selection of works by contemporary African artists that confirms the diversity and vitality of expression in black Africa today. Featuring artists living and working in sub-Saharan Africa, 100% Africa seeks to give support and exposure to creative artists fully committed to the continent’s future. The exhibition invites visitors to take a journey through more than 15 countries, providing an unusual, largely unexplored vision of art in Africa.

The idea of contemporary African art itself stems from a recent Western viewpoint, one that became significant on the international scene only in the late 20th century. In the age of colonization from the 19th century, art production in what were known as the "underdeveloped" countries was relegated to the level of folklore and crafts, while the category of contemporary art was reserved for Western works, artists, critics, and researchers. Yet academic art similar to the Western model did exist in Africa, the product of colonial and postcolonial teaching.

In the late 1980s, contemporary art worldwide grew more visible and began to be seen from a geographical standpoint, with interest focusing on intercultural relations and notions of universalization. A whole segment of contemporary art creation was at last to enter Western cultural life and consciousness. In 1986 André Magnin, curator of the Contemporary African Art Collection and curator of the exhibition, began researching and systematically exploring the "forgotten" continents—Africa, South America, Asia, and Oceania—in order to organize his seminal exhibition Magiciens de la terre at the Centre Pompidou and Grande Hall at La Villette in Paris in 1989.

This first truly international exhibition brought to light a host of surprising, unconstrained, and completely unfamiliar works. Since then, they have enjoyed international publicity and have won themselves a place in a world history of the arts.

The Contemporary African Art Collection

Magiciens de la terre showed contemporary artists from all continents on an equal footing for the first time. Established in the wake of this landmark event, the Contemporary African Art Collection (CAAC) is today the largest and most visible private collection of contemporary African art anywhere in the world. Fruit of the enthusiasm of Jean Pigozzi and of his encounter with André Magnin, the Collection includes artists from all generations now living and working in sub-Saharan Africa. "Before 1989," says Pigozzi, "I had no idea that Africa housed such a wealth of contemporary creation."

Devoted to contemporary African art in all its forms, the Contemporary African Art Collection in Geneva organizes and participates in individual and group exhibitions in modern and contemporary art museums the world over. But it is not in itself museum-oriented, nor does it aim to represent comprehensively all art trends in Africa. Rather, it is Pigozzi’s personal adventure, a passion that is now embodied in an international-class collection noted for its diversity and its demanding, rigorous, and sturdily independent selection criteria, as well as the relationships developed between the collection and the artists represented.

The relative absence of contemporary art museums, collectors, and galleries in Africa makes such personal relationships with the artists fundamental. Since 1986, when curator André Magnin began his research for Magiciens de la terre, the advent of the new technologies has revolutionized artistic production in Africa. Now the continent’s artists can contact each other, exchange ideas, and take part in the world’s most prestigious contemporary art events. This "revolution" has made a significant contribution to the acceptance and recognition of African art today.

100% Africa

This exhibition presents 25 contemporary African artists who live and work in sub-Saharan Africa. Painters, draftsmen, photographers, sculptors, and video artists from several generations are featured, including artists of international renown like portrait artist Seydou Keïta, painters Chéri Samba, George Lilanga, and Richard Onyango, the encyclopedist and universalist Frédéric Bruly Bouabré, the unclassifiable Bodys Isek Kingelez and Romuald Hazoumé, as well as younger, highly promising artists such as Abu Bakarr Mansaray, Titos Mabota, Pathy Tshindele, and Calixte Dakpogan, in an installation by leading Italian designer Ettore Sottsass and by Marco Palmieri, a prominent member of Sottsass’s team.

Most of these artists live in the major cities and produce figurative, narrative, or even didactic art, remaining close to their public, local, and world events. These snapshots of their surroundings may perhaps amount to a contemporary form of knowledge transmission inherited from the African oral tradition. It’s what people living in Kinshasa call "radio-trottoir" (a French-African term roughly equivalent to the "grapevine").

Other artists live deep in chaotic quarters and try to escape from the places where they live, from their daily lives, by dreaming. They invent "intergalactic", visionary machines to take them into another world.

Finally, some artists, particularly sculptors, live rooted in their home lands, perpetuating the creation of objects and enhancing their native traditions, beliefs, tales, and legends, or inventing ghostly universes.

The selection of works in 100% Africa highlights the importance of collective issues and shows that the idea of community continues to be an unavoidable reality of life in Africa. One of the most visible and enduring features, often vindicated by contemporary African creation, is that, while aspiring to international acclaim and understanding, artists are profoundly influenced by their surroundings, orienting their vision towards their immediate environment.

The Bété Alphabet (1990–91), one of the essential works by the universalist artist from the Ivory Coast Frédéric Bruly Bouabré, was conceived primarily for the Bété people, who have no writing, with the ultimate objective of applying to all the world’s languages. The artist has said that African traditions and the reality of life in Africa "have for me a radiant beauty that cries out to be interpreted and presented with pride to inform and instruct mankind." Prestigious Congolese painter Chéri Samba, a founder, with Chéri Chérin, Moke, and Bodo of "popular" Zairian painting, describes his art as being "impregnated by my surroundings. It comes from the people, it concerns the people and is addressed to it. Whatever his origins, an artist must make himself understood the world over."

Fellow Congolese artist Bodys Isek Kingelez, who lives in the center of the sprawling, chaotic city of Kinshasa, has an aesthetic and poetic commitment that leads him to question the human condition and to place his art at the service of the community, with a view to creating a new world. Through his visionary, utopian cities he conveys the idea that "art is elevated knowledge that is party to the best future open to the community."

Defining himself as a nomadic contemporary artist, Romuald Hazoumé from Benin has won recognition for his "canister masks," which call daily life into question while proposing a radical interpretation of the madness of the world today.

It feeds off history, cultures, beliefs, voodoo, and the vocabulary of initiation to determine works that condemn corruption in Africa and stigmatize modern slavery and the politics of Western countries with regard to Africa.

The late Madagascan artist Efiaimbelo produced sacred art, considered the most prestigious on the island. His refinement and inventiveness enabled him to keep the art form alive, and his aloalos, traditional funerary steles that adorn the tombs of the rich or a spiritual chief, are more an homage to life than death. The upper parts of his aloalos recall the major events in the life of the deceased and the life, tales, and legends of the clan. The work of Efiaimbelo was conceived as a receptacle of knowledge and wisdom to be transmitted to younger generations.

African photography had to wait until the 1990s to win international recognition. Its most representative figures, including Keïta, Malick Sidibé, J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere, and Depara, are portrait photographers and reporters who are witnesses to history and recorders of major social events.

Seydou Keïta, Mali’s great portrait photographer, photographed many of the inhabitants of the country’s capital, Bamako, between 1948 and 1962. The thousands of portraits by Keïta make an exceptional testimony of Mali society of that time. Beyond their obvious sociological interest, Keïta’s photographs are undeniable works of art. His reputation is founded on the quality of the images he produced and the originality of the poses he made his models take. His oeuvre has taken its rightful place alongside the works of the finest contemporary portrait artists.

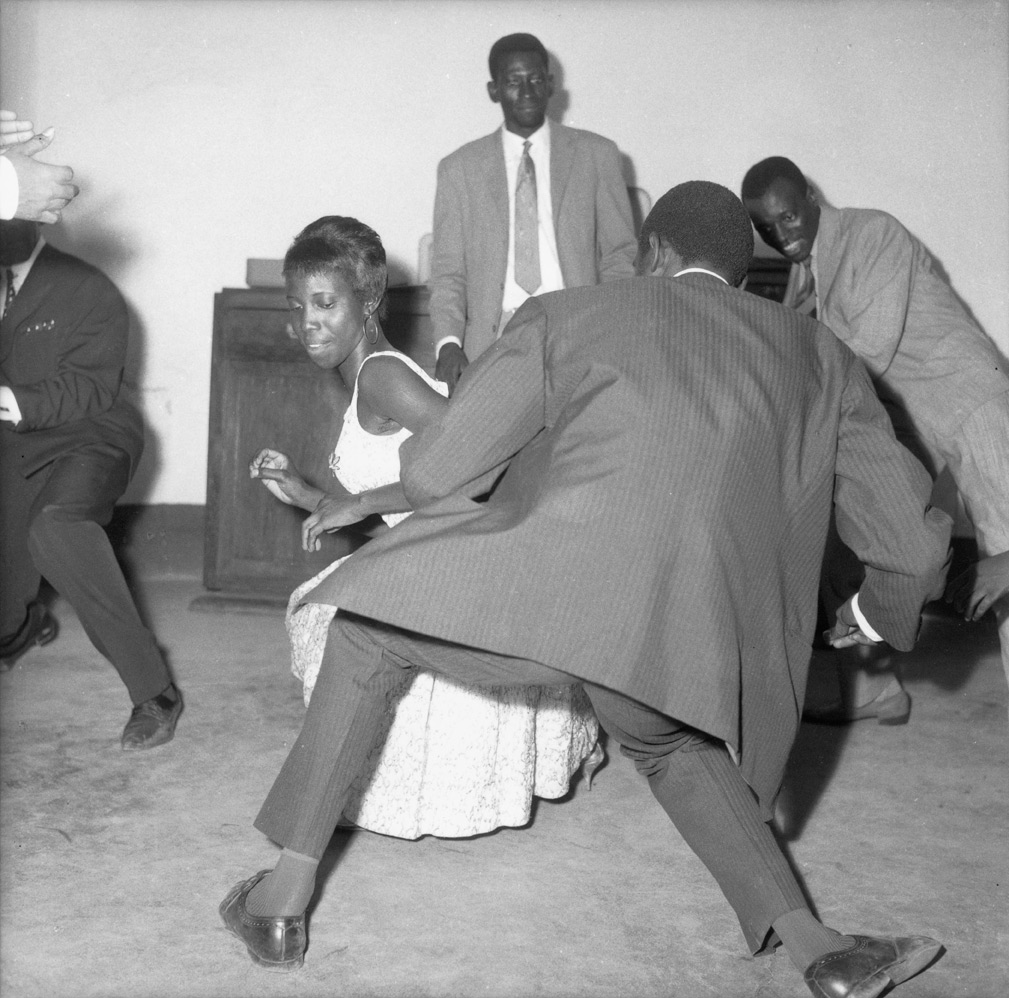

A new generation of photographers emerged in the ebullient 1950s that was totally involved in cultural and social life; its members played leading roles in society while acting as witnesses to it. Malick Sidibé from Mali and the Congolese photographer Depara accompanied youngsters as they discovered European and Cuban music and dance, dressing in Western-style clothes and trying to outdo each other in elegance.

Their files are a treasure house of exceptional information about the early years of decolonization and their local reports offer images brimful of reality, snapshots of daily and family life and leisure.Nigerian photographer Ojeikere embarked on a unique artistic project concentrating determinedly on African hairstyles, which he considers genuine creations. For 35 years he has stuck to his selfimposed task, and the result is an impressive archive of the hairstyles in his country, a unique legacy and a collective memory. He has revealed to us their diversity and incredible beauty. In fact his work unites anthropology, ethnography, and, above all, aesthetics.

Without a profound knowledge and understanding of the historical, political, sociological and cultural context in which these artist from black Africa work, 100% Africa would not have been possible. The works included in the exhibition bear witness to an explosive fusion of tradition, beliefs, and cultural exchanges past and present, a fusion that escapes a legacy that seeks to circumscribe them to its own history. Rather than just considering African artists from the perspective of their origins, today we need to appreciate them for the richness, singularity, and sheer power of their art.

Malick Sidibé

Dancing Twist (Dancer le Twist), 1965

Gelatin silver print

100 x 100 cm

Courtesy of C.A.A.C. – The Pigozzi Collection, Geneva

© Malick Sidibé