NEO-IMPRESSIONISM

The Neo-Impressionists debuted as an entity in a gallery of the Eighth (and last) Impressionist Exhibition in Paris in 1886, led by Georges Seurat. That same year, Félix Fénéon, an art critic and champion of these artists, coined the term “Neo-Impresionism” in a review. When Seurat died at an early age, Paul Signac took his place as the leader and theorist of the movement. The principal Neo-Impressionists—Henri-Edmond Cross, Maximilien Luce, Seurat, and Signac—were joined for a number of years by the former Impressionist Camille Pissarro as well as other like-minded artists, such as Belgian painter Théo van Rysselberghe, from nearby countries.

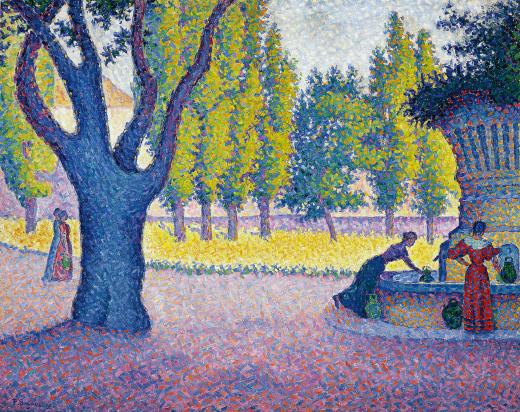

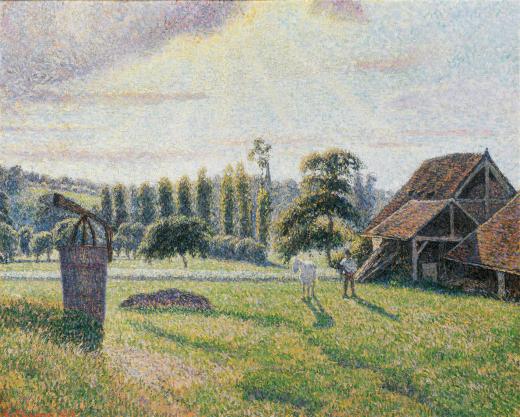

These vanguard painters looked to theories of color and perception to create visual effects in Pointillist canvases, among these the optical and chromatic methods developed by scientists— particularly in publications by French chemist Michel-Eugène Chevreul and by American physicist Ogden Rood. This modern, revolutionary painting technique was characterized by the juxtaposition of individual strokes of pigment to evince the appearance of an intense single hue. By thus orchestrating complementary colors and employing mellifluous forms, the Neo-Impressionists rendered formally unified compositions. The representation of light as it impacted color when refracted across water, or filtered through atmospheric conditions, or rippled across a field, was a dominant concern in their works.

Most of the Neo-Impressionists shared left-wing politics, evident, for example, in Pissarro’s and Luce’s depictions of the working classes. The idealized visions of anarcho-socialism or anarcho-communism were also manifest in the utopian scenes that the Neo-Impressionists frequently represented in their works, which often married ideological content and technical theory. But even when not guided by political objectives, the Neo-Impressionists’ shimmering interpretations of city, suburb, seaside, or countryside reflected places of harmony.