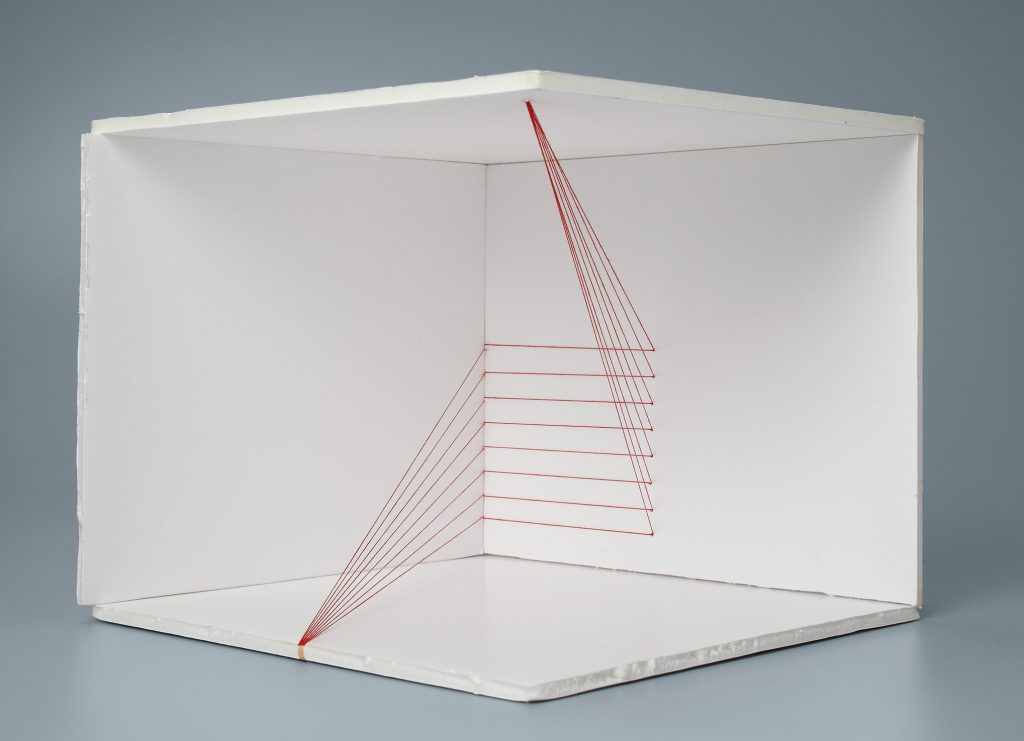

Spatial Projects (Proyectos espaciales) series, 1990

Spatial Projects (Proyectos espaciales) series, 1990

Red linen thread

Dimensions variable

Courtesy of the artist

© Esther Ferrer, VEGAP, Bilbao, 2018

“I call many of these projects ‘spatial projects’ because, when I make them, my ‘raw material’ is actually space [...] Because both installations and performances have, as I see it, three basic elements: time, space, and presence. Even though we perceive them differently, they are the same [...]” [1]

Artist Esther Ferrer (Donostia/San Sebastián, 1937) created a series of installations influenced by minimalism and conceptual art and titled them Spatial Projects (Proyectos espaciales). In most of these installations, the artist uses a simple, fragile, meticulous aesthetic to reflect on the construction of space. Ferrer takes small, insignificant, commonplace objects such as thread, nails, cables, rubber bands, and ropes, and reuses, relocates, and gives them new meaning in these works. In this way, Ferrer manages to draw in the void with minimum materials, which she alters, manipulates, and assigns new attributes in order to reflect on the void and its possible occupation.

The majority of her Spatial Projects are based on small scale models with cardboard or foam board structures that represent spaces in which the viewer’s perception is altered. Transferring her designs to a real, large, physical space is not a priority for the artist, because she feels that the creative process is the most interesting part. Thus, if the scale model works, Ferrer considers the work finished. [2] Some of her Spatial Projects never made it past the model stage, and this exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao is the first time they have been produced on a larger scale and shown to the public.

In this piece from the Spatial Projects series, Ferrer reveals one of her priorities: to keep space transparent, avoiding any hint of thickness, opacity, or real volume that might limit the spectator’s field of vision. [3] To this end, she makes thread—a lightweight, flexible, ordinary material—the basic component of her creation. That choice allows her to reveal alterity and repetition in time, while also showing how space can be utterly transformed by a minimum of elements. [4]

When creating her Spatial Projects, the artist attaches the threads to the different planes of the scale model—the walls, ceiling, and floor—and measures the distance between each anchoring point so that, when they are stretched taut, they resemble lines that crisscross the space forming geometric patterns. In this piece, the lines run parallel to the wall and break away at an angle, creating a sense of rhythm and a virtual space.

Referring to this work, Ferrer talks about how she arranged the material methodically, creating a mathematical system. The use of mathematical precision allows her to produce several works for the same series, exploring different nuances in each one. By varying only a few minute details, such as the number of threads or the distance between them, the artist completely alters the underlying mathematical concept of each installation. In this way she obtains an infinite variety of results, with different rhythms and directions that alter the perception of space and how it is traversed.

In the summer of 1972, the American experimental composer and musician John Cage and the Zaj collective (comprising Esther Ferrer, Walter Marchetti, Ramón Barce, and Juan Hidalgo) met at the Pamplona Encounters, an international art festival that brought together over 350 artists from a variety of disciplines, including electronic art, performance, video art, poetry, painting, sculpture, film, and experimental music. Impressed by the Spanish group’s aggressively bold and groundbreaking proposals, Cage invited them to participate in John Cage’s Train. In Search of Lost Silence; this collective happening or performance took place over three days on board a train that left Bologna, Italy, each day for a different destination. While her colleagues handled the sound side of the project, Ferrer transformed the railway car with a web of threads attached to different points of the interior furniture that made it difficult for travelers to get by, thus involving them in her intervention.

[1] http://afasiaarchzine.com/2016/04/esther-ferrer-4/

[2] http://angelsbarcelona.com/files/10_esther_ferrer_expo_dossier.pdf

[3] Audio guide to the exhibition Esther Ferrer. Intertwined Spaces at the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao.

[4] Audio guide to the exhibition Esther Ferrer. Intertwined Spaces at the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao.

Preguntas

Take a close look at this installation. What do you see? How would you describe the work? What stands out to you? Have you ever seen anything like it? How does it make you feel? The work is called Spatial Projects. Why do you think the artist chose that title? If you could change the title, what would you call it? If you could add sound to the structure, what do you think you might hear when exploring it?

How do you think the artist created the work? Have you seen these materials somewhere else? Where? How would you define them? Describe how you imagine it step by step. Referring to this work, Ferrer talks about how she arranged the material—thread, in this case—in a very methodical and orderly way, creating a mathematical system. What connection do you see between her work and math? What do the lines suggest to you? Why do you think she decided to put them at that height and give them that shape? How would your perception of the work change if the threads were another color or arranged a different way? How would you arrange them?

Spectators can enter this installation at the Museum, being very careful not to damage the work. Why do you think Ferrer wants us to explore her piece? If you touched it, how do you think it would feel? It’s important to Ferrer that her works alter each viewer’s perception of space. How do you think she manages to achieve that? In your particular case, how has it changed your perception of the space?

As part of her creative process, Ferrer makes scale models of her installations. Most of them are never recreated in large spaces like this one. On this topic, the artist said, “I’ve never been very interested in producing my projects on a large scale in a real space; if the model I made works, the piece is done. If I have the chance to produce it in a real space, great; but if not, it’s no big deal. For me, art is a process.”[1] What do you think about her idea? Do you believe a work can be considered finished if it never moves past the scale model stage? Explain why or why not. What do you think about the idea of art as a process? To what extent do we tend to value the outcome of an artistic process more than the process itself? Why might we consider this way of valuing artworks fair or unfair?

[1] https://www.macba.cat/es/proyectos-espaciales-series-7-5127