Chillida: 1948–1998

04.20.1999 - 09.12.1999

The sculptures of Eduardo Chillida (b. 1924, San Sebastián; d. 2002, San Sebastián) are among the most important of any Spanish artist's work. The retrospective exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao to mark the artist's 75th birthday is the first of its kind to be staged by a Spanish museum. Exhibition curator Kosme de Barañano also supervised the 1992 retrospective held at the Palacio de Miramar in San Sebastián, Chillida's home town. Sculptures by Eduardo Chillida are to be found in most major museums in Germany (Mannheim, Berlin, Frankfurt, Düsseldorf, Münster, etc.), Switzerland (Basel, Zurich, Geneva, Winterthur, etc.) and the United States (New York, Houston, Dallas, Washington DC, Chicago, Pittsburgh, etc.).

His work has been discussed and analyzed by art historians, museum directors, a number of poets, including Octavio Paz, Gabriel Celaya, José Ángel Valente, Jacques Dupin, Claude Esteban, Edmond Jabes, and Yves Bonnefoi, and philosophers such as Gaston Bachelard, Martin Heidegger, and Rene Thon. Many of Chillida's works are to found in public places all over the world. Outdoor sculptures of his interact with the natural landscape are, for instance, Combs of the Wind in San Sebastián, The House of Our Father in Guernica, The House of Goethe in Frankfurt, The Monument to Tolerance in Seville, and In Praise of the Horizon in Gijón.

The Guggenheim Museum Bilbao retrospective is an enlarged version of the exhibition originally held at the Museo Nacional Reina Sofía in Madrid and presents some 200 works by the artist from 1946 to the present day, thus covering more than 50 years of a creative career largely concentrated in two genres: sculpture and drawing. The selection covers all the materials and stages of the artist's development and is divided into four sections.

The first section includes large-scale works, as the gallery spaces available for the exhibition at the Museum can take works up to 11 tons, which means a number of major works in steel are excluded. A second section deals with works in fired chamotte which the artist calls lurras and are an important part of his production; the third section is given over to works with or on paper, the reliefs (or gravitations, to use the artist's own term), and the fourth and final section includes his drawings.

For this last section, a careful selection of 100 works has been made that covers the lines and marks made in pencil or ink and the outlines achieved with scissors cuts and collage. The idea was to use the 100 drawings selected to create a closed world of works in themselves, rather than to show a group of preliminary drawings or sketches. This exhibition within the exhibition is an attempt to provide a double reading of the visual world of Eduardo Chillida, of the relation to the history of Western art of the basic concepts in his form of visual perception. The works of hung paper, called gravitations, are considered here as part of his production in sculpture-reliefs constructed with paper, not just as simple drawings. In this respect, the exhibition is less a run-through of the artist's working life and more an attempt to explain to the observer the basic ideas and concepts that Chillida questions, reexamines, and vivifies, in other words, the concepts to which he gives new form. Chillida´s work does not pose problems of modeling, or representation, or expression, but looks rather at metaphysical issues, i.e., issues that have more to do with the formulation (through the material) of concepts such as limit, vacuum, space, and scale. All of these are interrelated and subject not only to the material (earth, steel, granite, etc.) in which they are expressed but also to the observer (his position, pathos or sensibility, and his tact).

The use of particular materials, explored and analyzed through the artist's hands, helps us to distinguish a more or less chronological stages in the artist's development. From his earliest essays in plaster to the works in chamotte , from the first attempts at modeling small figures to the configuration of public spaces, from the earliest doubts and projects in 1948 to the present day, we see the path Chillida has traced, sweated, suffered, and enjoyed. It is a path literally constructed in iron, steel, wood, alabaster, concrete, and earth. This is not to say that he has not used other materials. In 1951 he worked on a relief in lead, in 1958 there was a brief incursion in bronze and in 1962 it was marble and granite. Curiously, Chillida's explorations of and experiences with materials are always done in relief. Among the etchings, woodcuts, and lithographs that make up his graphic oeuvre, there are a few silkscreens, dry points, and aquatints but, given the range and extent of his graphic production, it was decided not to include them in the present exhibition.

What the exhibition does provide is a close look at Chillida's creative processes and the modes of production he has used; in that sense, it could almost be described as an encyclopedic overview of artistic techniques throughout the ages. It is true that Chillida has concentrated on materials that are not in themselves classical (bronze and marble are the usual materials in his oeuvre). What he has done is to use new, twentieth-century materials such as steel or concrete with a sort of classical delicacy and tact. In a rather oblique way, the materials help us to order his artistic work. In fact, Chillida's work is probably better approached via the modes of production used than the subjects or themes he deals with. From the beginning, construction or experimentation has been based on repetition and the production of series. Some of these series are associated with a particular moment in the artist's life and range over specific years or months: other series are a permanent feature of his entire career; still others make occasional appearances at certain moments throughout his lifetime, before disappearing again. One often sees a new motif appear and is able to follow the successive transformations it undergoes, and the gradual mutations of the form in which the artist acts on and against the material. In this sense, repetition in Chillida does not imply either the trivialization of his exploratory urge or the reduction of his gesture to a purely technical virtuosity. Chillida's work is a permanent questioning of the material.

As he himself says: One can never know enough / The unknown and its call / Lies even in what we know.

Kosme de Barañano, exhibition curator

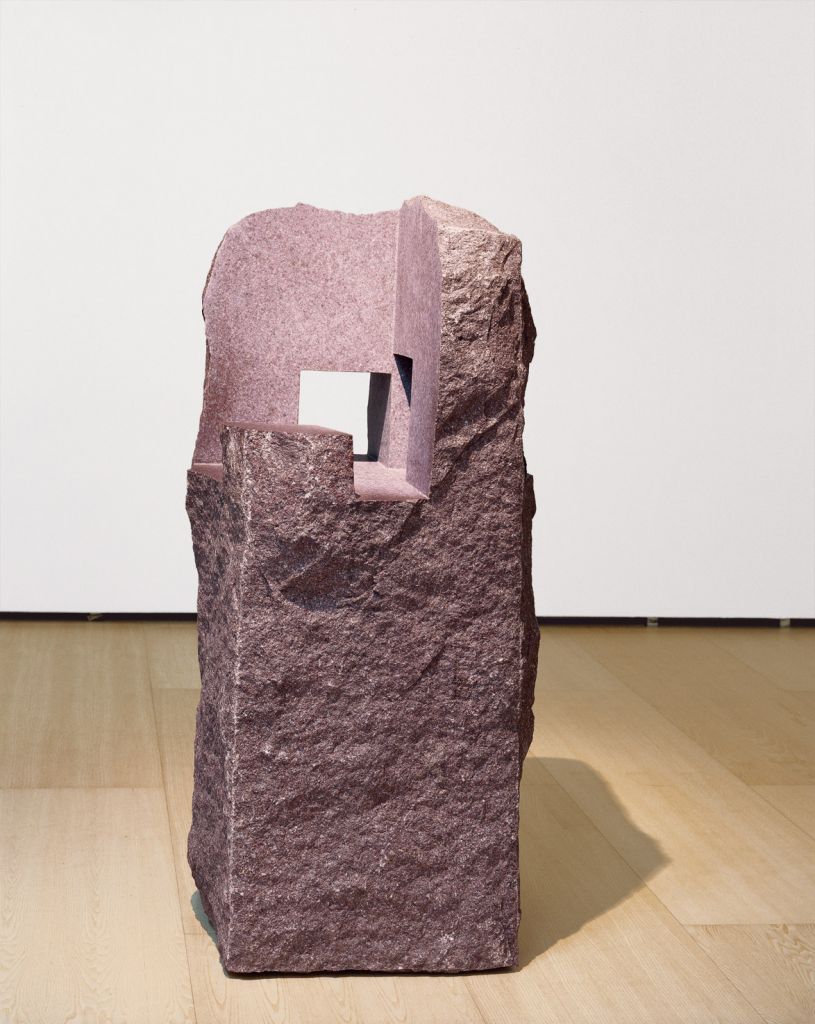

Eduardo Chillida

Space for the Spirit (Espacio para el espíritu), 1995

Pink granite

173 x 85 x 91 cm

Guggenheim Bilbao Museoa