SPACE AND MATIÈRE: CHARDIN AND MORANDI

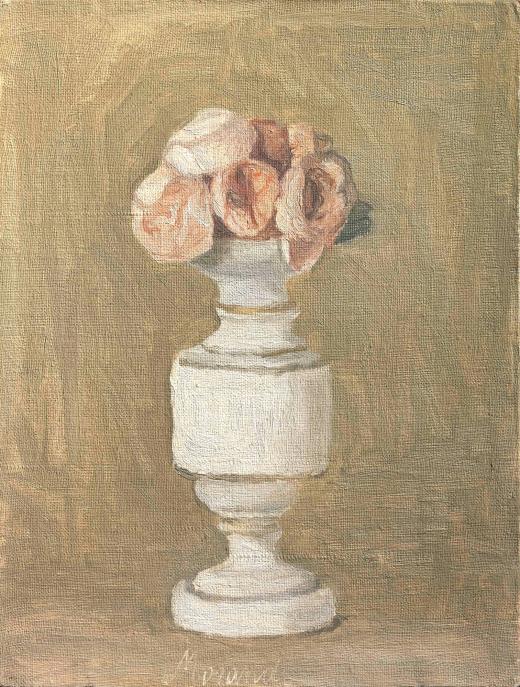

Among the Old Masters, Morandi openly revered and applauded the French genre painter Jean-Baptiste Siméon Chardin. When first studying Chardin, Morandi could well have encountered the article published in 1911 by the art critic Henri des Pruraux in the avant-garde journal La Voce, in which the author claimed that Chardin had invented the modern self-referential still life. In 1932, the periodical Valori Plastici distributed André de Ridder’s amply illustrated monograph in Italy. Morandi tacked reproductions from this book on the walls of his studio so as to have them constantly in sight as examples. These illustrations allowed Morandi to gain insight into Chardin’s artistic process. The French master worked in series with different variations, and he recycled objects he owned in his artworks. Morandi also adopted these strategies, returning time and again to the same jugs, bowls, bottles, and boxes, making slight alterations to their arrangements.

Chardin continued to resound throughout Morandi’s career. In his 1960 interview with the critic Edouard Roditi, the artist described him as “the greatest painter of still life” because “he never relied on trompe-l’oeil effects. On the contrary, with his pigments, forms, sense of space, and what the French critics call his matière, he managed to suggest a world that interested him personally.” In Chardin, Morandi found someone in history who was a true equivalent, concerned with the same issues: the first artist to tackle the question of painting in itself through a specific genre—the still life—with the goal of understanding its full potential.