When, in the mid-1950s, Richard ArtSchwager (b. 1923, Washington DC; d. 2013, Albany, USA, 2013) ventured into the realm of art, many international artists were starting to move away from abstraction, creating new movements in New York, London, and Paris. Both sides of the Atlantic witnessed the birth of new approaches to art-making in close connection with everyday objects, while advertising and television dominated popular culture.

Pop Art emerged during the 1950s in England, but it particularly took over the New York scene during the 1960s. Andy Warhol’s Campbell Soup Cans became iconic of the new art that turned camp, high and low culture, banality, and taste upside down.

Throughout the 1960s and alongside Pop Art, a trend labelled Minimal Art–or “Literalism,” “ABC Art,” among other attempted names—also spread throughout the US. In Minimal Art, material shapes devoid of reference were the absolute priority; geometric organization was favored over subjective expression; and industrial manufacturing imposed itself over craftsmanship. Donald Judd, Dan Flavin, Carl Andre, and John Chamberlain were among the leading figures of this movement.

Another new avant-garde developed during this time: Conceptual Art, whose principles derived from the simplicity of Minimalism, serial composition, and an ironic sensitivity toward descriptive language, emphasizing communication over production. Joseph Kosuth’s series Titled (Art as Idea as Idea), as well as Sol LeWitt’s Structures, and Robert Barry’s invisible works, are good examples of this influential movement.

At that time, Artschwager wanted to create “paintings for the touch” and “sculptures for the eye.” His artworks blurred the boundaries between Pop, Minimal, and Conceptual art but he wanted his aesthetic drive to remain “not classified” as a specific trend.

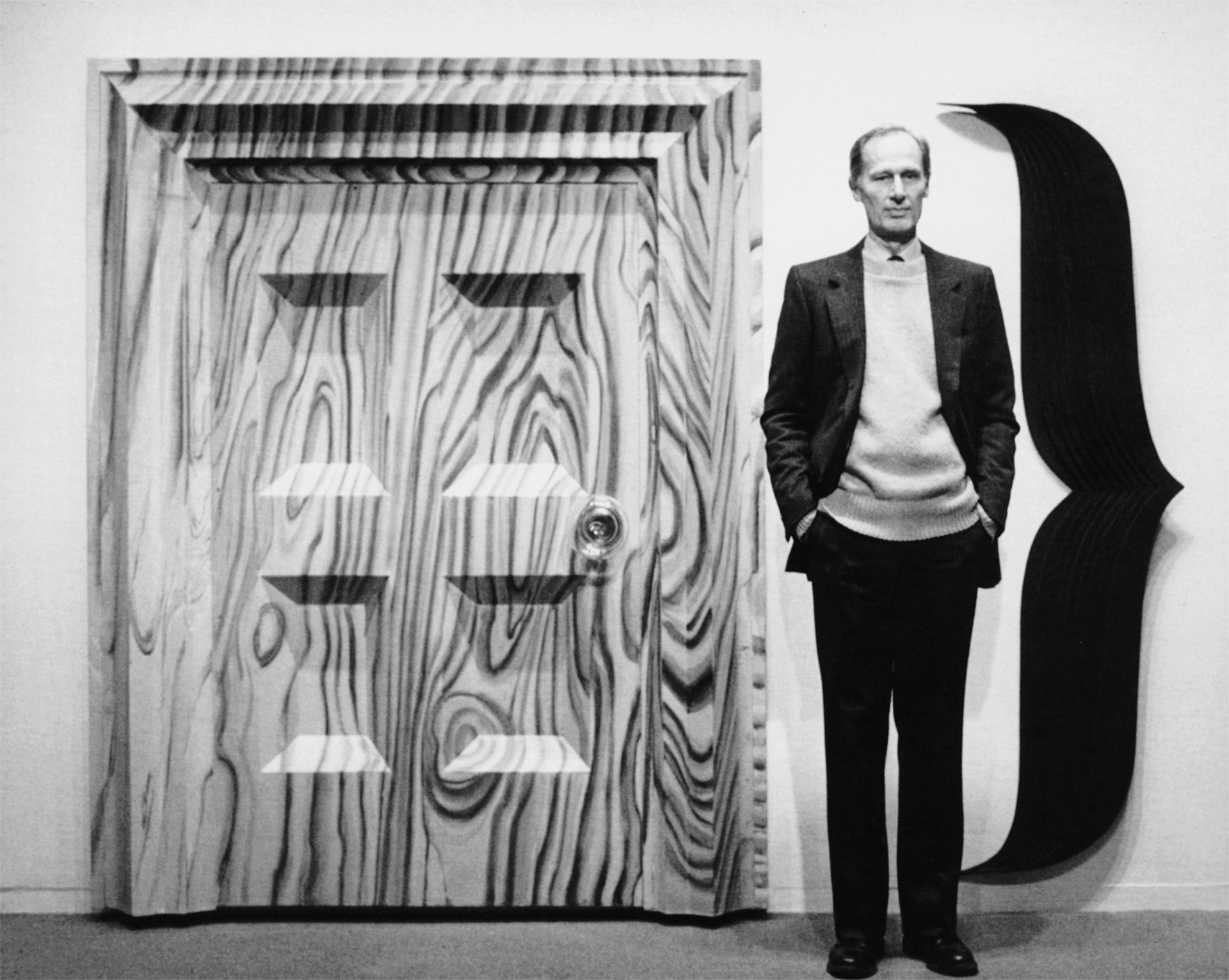

Artschwager’s main focus is our immediate surroundings and the space we inhabit, where not everything is what it seems to be. Through newly-developed commercial materials for domestic use, like formica, Celotex, or rubberized horsehair, Artschwager created a feeling of strangeness in his sculptures of common, apparently ordinary household items, like doors, windows, tables, basket mirrors, rugs, etc.

In Europe, a very different socio-political context gave birth to movements that addressed everyday life in different ways.

In Paris, around 1960, the Nouveaux Réalistes produced their own version of Pop Art. This group of young artists used found materials and debris of consumer culture to produce works of art that heavily referenced street life.

In 1963 in West Germany, Gerhard Richter, Sigmar Polke, and Konrad Lueg formulated Capitalist Realism. Lueg would later open the Konrad Fischer Gallery—using his mother’s maiden name—and exhibited works by Artschwager among many other Conceptual and Minimal artists. Richter, Polke, and other Capitalist Realists drew images from the mass media in a similar manner to Pop Art, and introduced critical nuances to the style known as Socialist Realism that dominated the Eastern block.

For many proponents of the trends that redefined the nature of the artistic object, a key historical reference can be found in Marcel Duchamp’s readymade. Since the infamous presentation of his Fountain in 1917, Duchamp announced a radically ironic approach to art based on conceptual, not material grounds. For him, a functional object, such as a bottle rack, a urinal, or a bicycle wheel, could be turned into art without transforming them physically—repositioning them was enough.

Richard Artschwager would, at a turning point in his life, quit his job as a cabinet maker to devote himself entirely to art. As an artist operating in the realms of painting and sculpture, he intended to create objects that were free from function and, at the same time, reflective on what function means in our spaces and lives. In this sense he invented the blps, signs meant to call attention to our surroundings. Set in different sizes and materials, blps may be installed on any surface and any location—hanging high and low, inside or outside the exhibition space.

Richard Artschwager with Door }, 1984

Photo: Ben Blackwell

As part of the Didaktika project, sponsored by BBK, the Museum offers educational spaces, online content, such as Did You Know…?, and special activities that complement the exhibitions with tools and resources to improve your understanding and appreciation of the artworks on view.