Soto studied at the School of Fine Arts in Caracas, where he became familiar with modern European art and discovered artists like Paul Cézanne and Pablo Picasso, whose schematic visions of reality revolutionized his own approach. Attracted by the European avant-garde movements, in 1950 he moved to Paris, where he was welcomed on arrival into Los Disidentes, a group of artists from the Venezuelan diaspora who were trying to renovate the art of their homeland by encouraging the most modern practices. During his first years in Paris, Soto earned his living by playing the guitar in various ensembles, and it was then that the group Los Yares was formed. His interest in musical compositional structures meanwhile inspired him to produce serial works and variations, and to develop his own color scheme.

In this context, the series of lectures organized at the Atelier d’Art Abstrait played a key role in Soto’s discovery of artists like Piet Mondrian and his austere orthogonal compositions; Kazimir Malevich and his radical proposal of monochrome white on black; and László Moholy-Nagy and his theories on movement, light, and transparency, published in his essay Vision in Motion. Crucial too was the artist’s encounter with the motorized optical devices of Marcel Duchamp, and particularly the Rotary Demisphere (1925), presented at the Galerie Denise René as part of the exhibition Le Mouvement (1955), in which Soto also participated, and where the term Kinetic Art was coined. Over the following years, Soto was to carry out further explorations of some of the ideas raised by these precursors, taking artistic investigation onto a terrain close to scientific experimentation and the philosophy of perception. Under the concept of the “fourth dimension,” Soto set about integrating time and the viewer’s movement into the artwork, and in so doing defined one of the mainstays of all kinetic art.

Soto assigned a key role to the viewer, since it is only through the viewer’s movement that the work is “set in motion.” His idea that the viewer can enter and form part of an installation culminated in the late 1960s with the creation of the Penetrables. Soto created works accessible to all, regardless of age or culture, without directly invoking any academic knowledge of art history. For the same reason, his work lent itself to the transformation of public spaces and the creation of collective aesthetic experiences, from the Muro cinético (Kinetic Wall, 1969), displayed at the UNESCO building in Paris, to the Sphère Lutétia (Lutetia Sphere, 1996), first presented in the same city three decades later, and now reinstalled for this exhibition outside the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao.

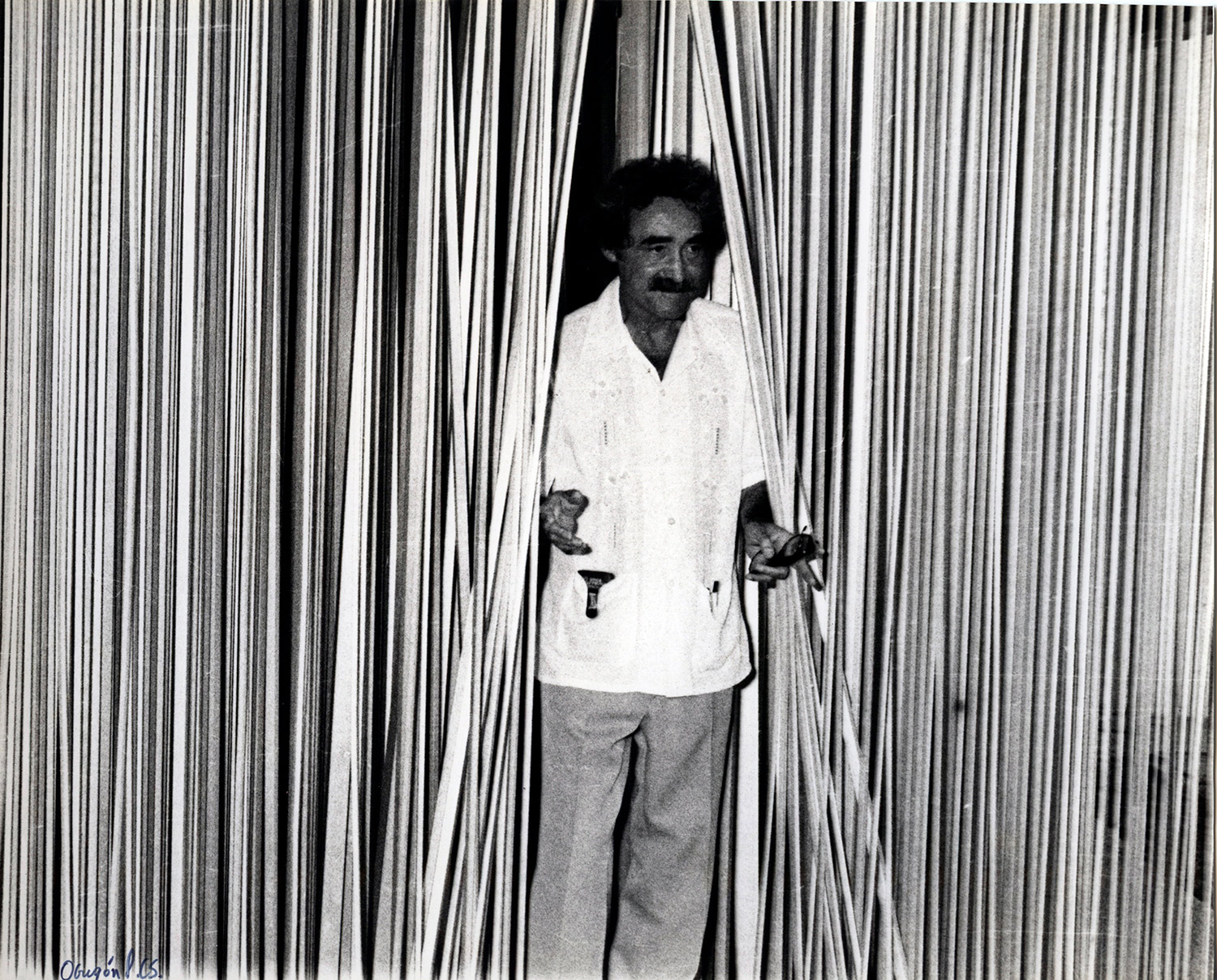

Photo: Copyright Luis Carlos Obregón